Git

Git is a distributed version control system that retains repository state snapshots and the relationships between them.

The canonical reference for git is the Pro Git book.

States in a git repository

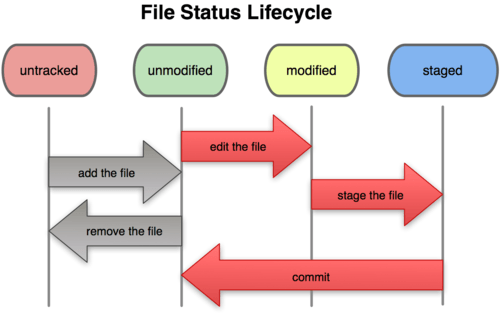

Files in a git repository exist in one of four states. This is shown in the following figure.

First, files can be tracked or untracked. Tracked files can be modified, changing from unmodified. If a file that is modified needs to be committed to the repository, it must first be staged. Staged files can then be committed, changing the state back to unmodified as far as git is concerned.

The discussion below shows the commands that are necessary to commit files.

How git works to retain version history

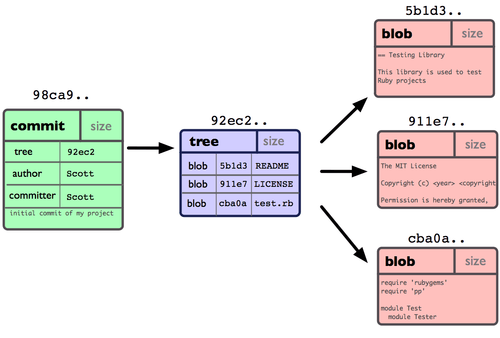

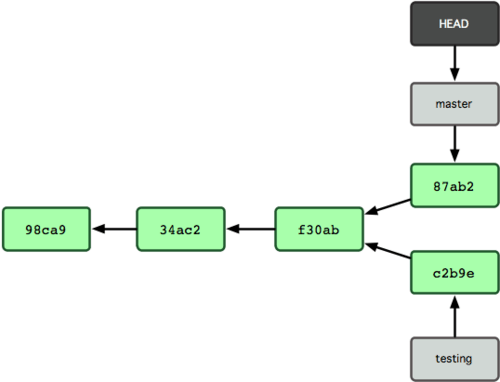

Each commit is a collection of data that is identified by cryptographic hash of the data and its metadata. In practice this is a commit structure which points to a tree structure which then points to a collection of blobs, where each of these individual structures is hashed and the hash is included in the containing structure.

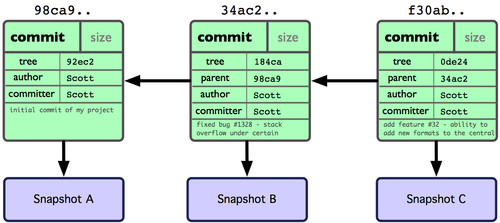

In the case of a repository with more than one commit, the commit datastructure will also contain a pointer to the previous version (called the parent), which is also hashed with the rest of the commit datastructure.

This means that if we know the most recent we can follow the parent links to the original commit. A commit may have more than one parent, but it is not possible for a commit to point to its children. This set of properties means that the git commit history is a directed acyclic graph.

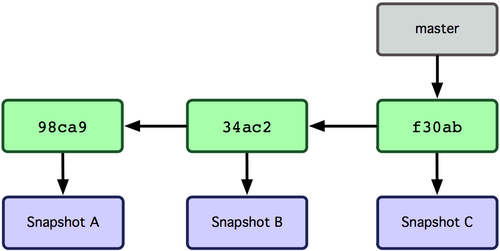

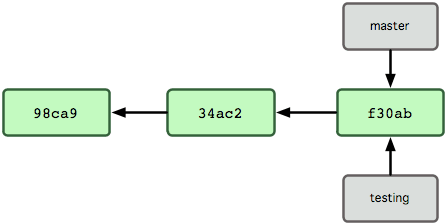

In order to be able to keep track of the most recent version or versions that are being worked on concurrently, Git adds the notion of a branch which is simply a pointer to the most recent addition. When you add a new commit, the current branch pointer moves from pointing to the previous commit to the new one.

The existence of branches means that a set of changes may be made to the repository concurently.

A second branch can be created to progress changes leaving the existing branch untouched.

$ git branch testing

(Normally git branch <branch> is not used to do this since you usually want to immediately change to the created branch.

Use git checkout -b <branch> instead.)

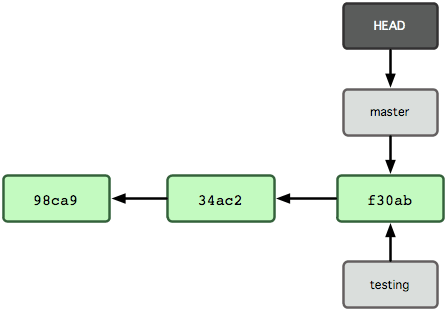

Git keeps a global state variable for the current branch, called HEAD.

Note that the HEAD points to a branch, not a commit, so in the example above, a commit would add to master and progress that branch.

Changing branch involves changing the branch that HEAD points to, although sometimes this may be an anonymous branch.

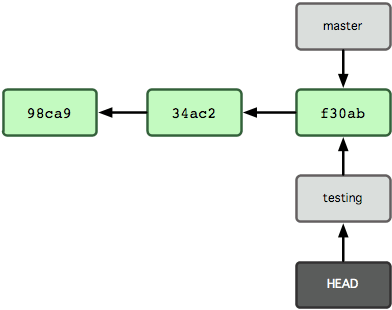

$ git checkout testing

Now, adding a commit advances the branch pointer, leaving the other branch where it was.

$ vim file.text # Create a new file - it is untracked at this stage.

$ git add file.text # Add the file - now it is tracked and staged.

$ git commit -m 'made a change' # Commit the file - now it is unmodified.

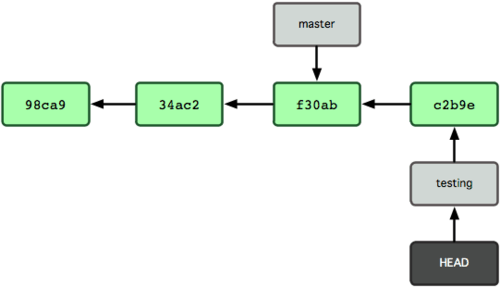

If the HEAD is then moved back to the master branch and another change is made, you will end up with divergent branchs.

$ git checkout master # Change to the master branch (file.text doesn't exist here).

$ vim file.text # Create a new file - again it is untracked.

$ git add file.text # Add the file - now it is tracked and staged.

$ git commit -m 'made other changes' # Commit the file.

These divergent branches can be brought back together in a merge operation. This is what makes it possible for more than one person to be working on a repository at the same time on different computers and have the results reconciled in the future.

On a different repository:

$ git checkout master

$ git merge iss53

You can see that under this kind of use, the repository only ever gains data; no data is lost during version changes.

During merging, there may be changes in divergent branches that are inconsistent with each other. This is called a conflict and requires manual intervention and will be discussed later.

A good visual reference that goes through a similar set of changes, and more, is available here.

Questions

- Why can a commit not contain a child or children pointer(s)?

Set-up

Now that you have git on your system, you’ll want to do a few things to customize your git environment. You should have to do these things only once; they’ll stick around between upgrades. You can also change them at any time by running through the commands again.

The following assumes that you have installed git for your platform.

Git comes with a tool called git config that lets you get and set configuration variables that control all aspects of how git looks and operates.

These variables can be stored in three different places:

/etc/gitconfigfile: contains values for every user on the system and all their repositories. If you pass the option--systemtogit config, it reads and writes from this file specifically.~/.gitconfigfile: specific to your user. You can make git read and write to this file specifically by passing the--globaloption.config file in the git directory (that is,

.git/config) of whatever repository you’re currently using: Specific to that single repository. Each level overrides values in the previous level, so values in.git/configtrump those in/etc/gitconfig.

Your identity

The first thing you should do when you install git is to set your user name and e-mail address. This is important because every git commit uses this information, and it’s immutably included in the commits you pass around:

$ git config --global user.name "My Name"

$ git config --global user.email my.email@domain.net

Again, you need to do this only once if you pass the --global option,

because then git will always use that information for anything you do on that system.

If you want to override this with a different name or e-mail address for specific projects,

you can run the command without the --global option when you’re in that project.

Your editor

Now that your identity is set up, you can configure the default text editor that will be used when git needs you to type in a message. By default, git uses your system’s default editor, which is generally Vi or Vim. If you want to use a different text editor, such as Emacs, you can do the following:

$ git config --global core.editor emacs

Your diff tool

Another useful option you may want to configure is the default diff tool to use to resolve merge conflicts. Say you want to use vimdiff:

$ git config --global merge.tool vimdiff

Git accepts kdiff3, tkdiff, meld, xxdiff, emerge, vimdiff, gvimdiff, ecmerge, and opendiff as valid merge tools.

Checking your settings

If you want to check your settings, you can use the git config --list command to list all the settings git can find at that point:

$ git config --list

user.name=My Name

user.email=my.email@domain.net

color.status=auto

color.branch=auto

color.interactive=auto

color.diff=auto

...

You may see keys more than once, because git reads the same key from different files (/etc/gitconfig and ~/.gitconfig, for example).

In this case, git uses the last value for each unique key it sees.

You can also check what git thinks a specific key’s value is by typing git config <key>:

$ git config user.name

My Name

Activity

Set up your git configuration following the instructions above.